The micro-location revolution promises more information for museums and their visitors than ever. But do we already have too much "stuff" in the museum? And how do we keep track of it all?

For most of my museum career I've worked on publications at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and while some would judge a book as a difficult project based on its length, scholarly density, or number of images, for me, it would come down to the amount of "stuff" in the book.

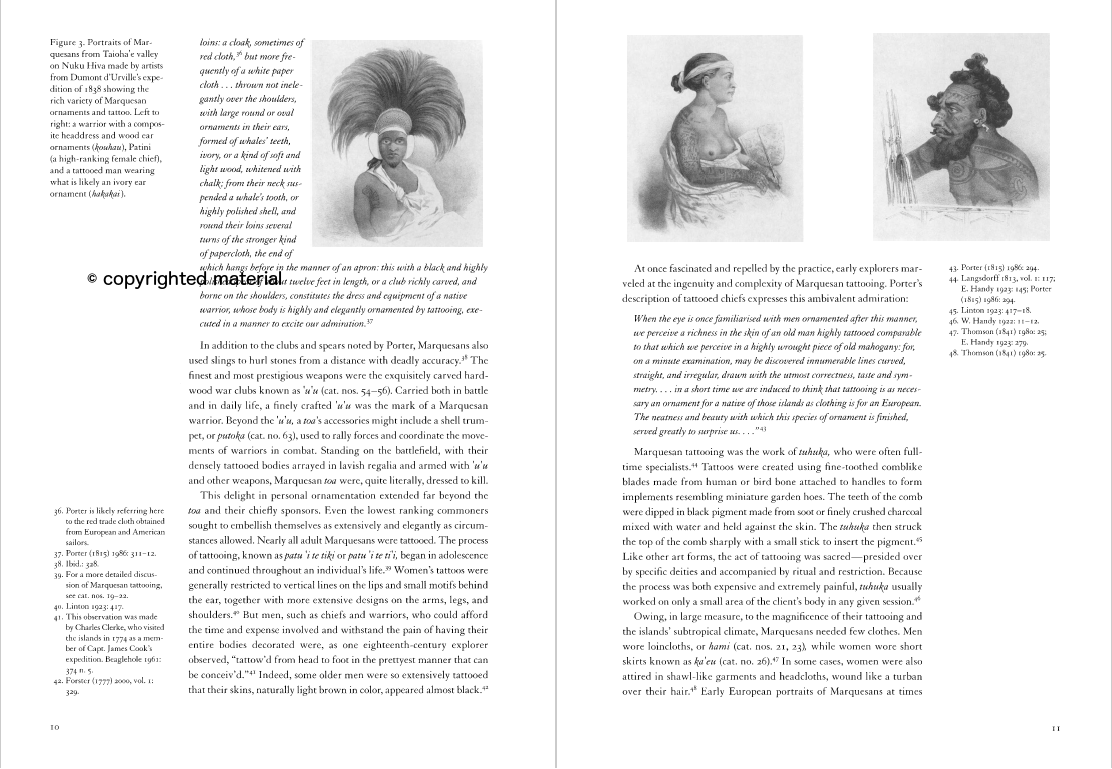

From a typesetter's point of view, there's a lot less stuff in 20 pages of this book I designed for The Met:

than even two pages of this book I typeset for The Met:

Each column from the latter publication has so much more stuff on it: images, captions, text of all different semantic styles and uses and meanings. It's a tremendous amount of work keeping that all straight.

Of course, there's automation, tags, and scripts to help. One of my first typesetting tools was a floppy-disk utility called WordLess Plus, which stripped out Word formatting and replaced them with Quark tags. (Stop. You'll be old, too.)

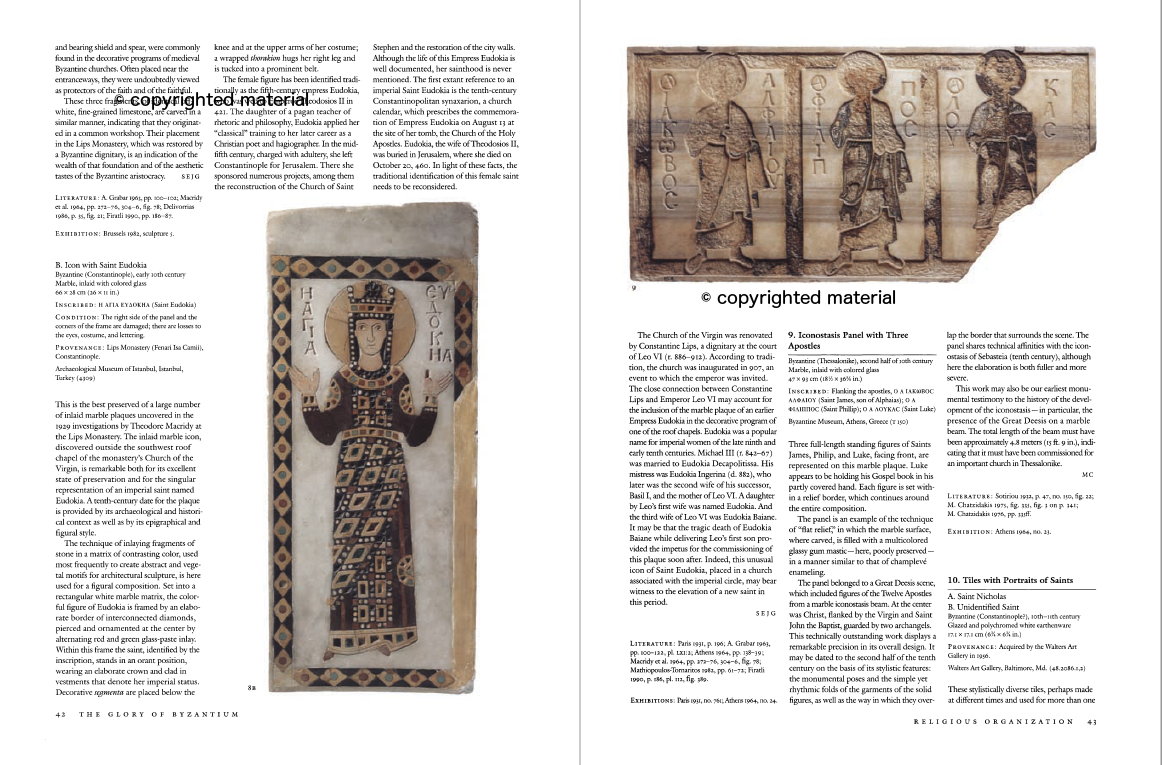

But a book like that can have, all told, thousands of images, text frames, styles, and other stuff. Keeping track of them are what workflow systems are all about, but even the best systems can't capture everything that everyone knows about all this stuff, especially when it all to go the printer and come back and get archived, maybe trotted out again for a reprint where some of it might be corrected. And that's just one part of the process; there are images to be ordered, photos to be shot, CMS data to be entered, text to be edited and changes tracked.

It's why I came up with this chart a few years ago for our publication workflow.

abandon sanity all ye who enter here …

Fasten your best practices, it's going to be a bumpy night.

And, to jump out a level, like the Powers of Ten film from Charles and Ray Eames, there needs to be this kind of organization at every scale in the museum world. A book becomes a thing to track in merchandising, exhibition planning, and membership, among other departments. And those departments are part of larger fundraising, budgeting, and staffing problems.

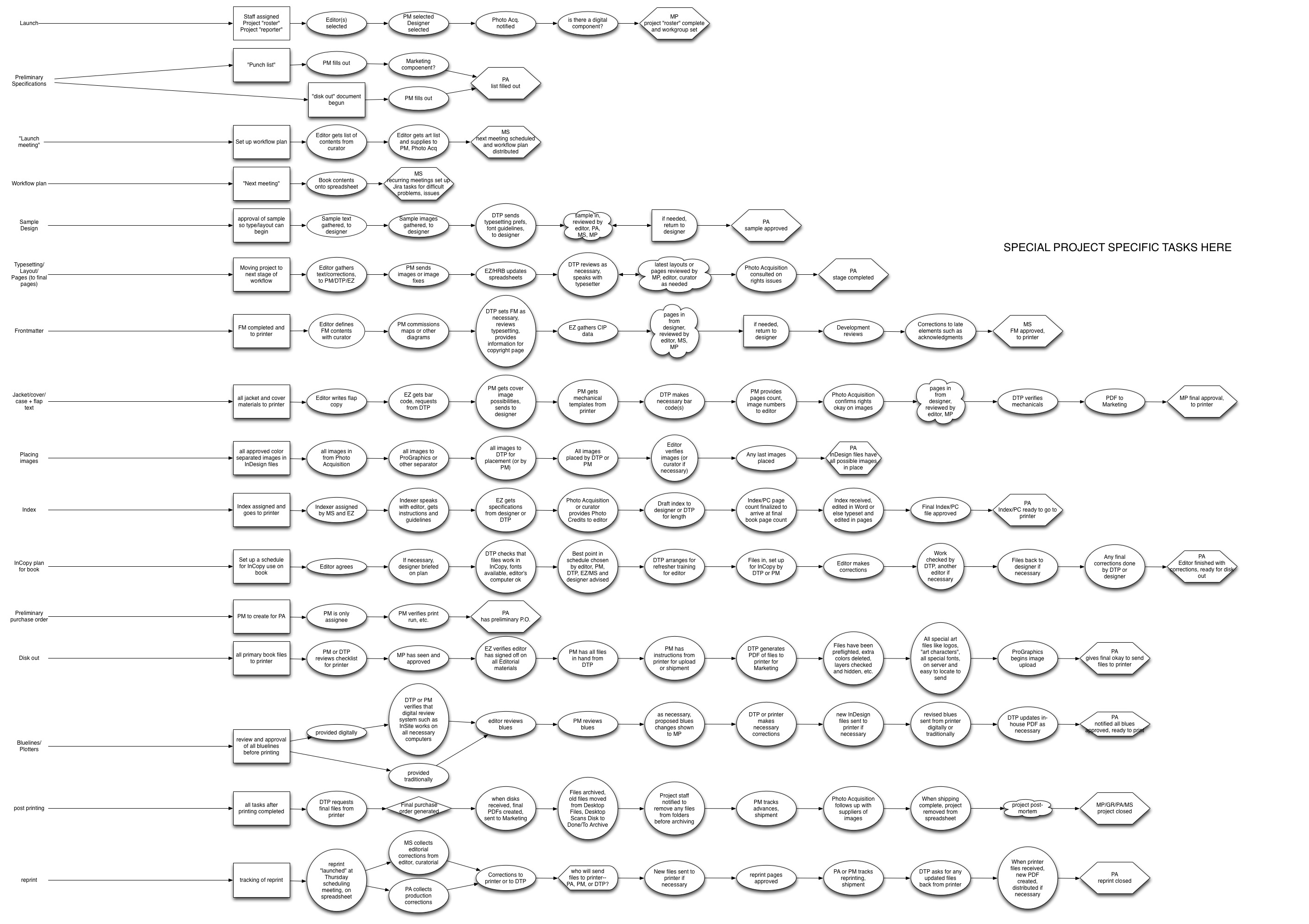

The point here is data. Those of our colleagues who think that data is a corporate word … no. Data is already here. Those pre-CMS index cards didn't sort themselves, nor did the data in our CMS's enter themselves. The question is, how do we want to organize it? (Them, to be old-school grammatically correct.)

Back in the day.

The question is important because data isn't a thing anymore, it's a mindset, a practice, a pact we make with each other to keep our stuff in a place where others can get to it when needed. Remember that pit in your stomach when that extra hard drive died, because you thought and hoped but wasn't a million percent sure that the contents were backed up somewhere else? Or that time when a boss said, dump all of that stuff, who needs it? (Or, conversely, keep everything, you never know when you might need it.)

It was 15 years ago that a colleague first told me to be ready to start adding XML to our InDesign files. And I've been ready, without actually doing it. After all, XML without a scheme(a) and a place to re-use that content is the essence of one-hand-clapping. (Or think of Addison's Alexander Graham Bell joke from Moonlighting: "Why am I inventing the telephone? No one else has one. Who'm I going to call?")

The XML is the easy part. Making it a habit is hard. And being willing to admit that maybe in a few years we won't want to tag in that way is even harder. Failure is brave.

And this is where micro-location, or beacons, come into the discussion. When we talk about collecting more data on our visitors by tying together our membership and sales and events systems like with Tessitura, or by having beacons guide people's audio experience like at SFMOMA, or some far-off dream of labels that respond to the user based on their preferred amount of information, we're talking behaviors—and not of our visitors, but of our staff.

And all this cataloging has ramifications for how staff are treated—and not just in salary, but in terms of working where it's most productive or even just given incentive to tell their bosses I have too much going on. And for our IT departments to find the tools that help colleagues navigate through these data waters.

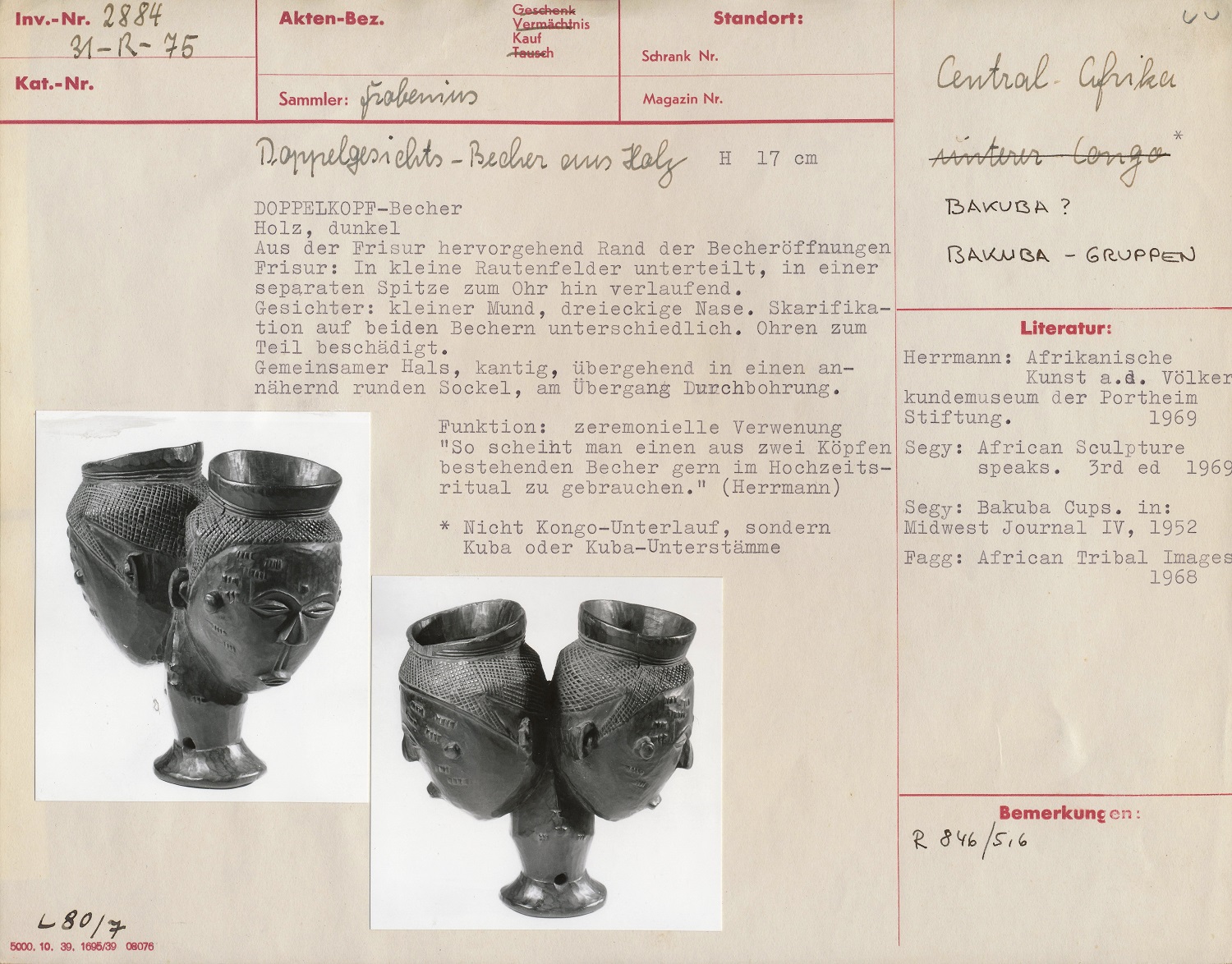

If we really want our museum objects to be smart, we need to empower them with the ability to make connections that we might not see. We already have grad students and interns … I mean, colleagues, tagging and keywording lots of stuff, but are we doing everything with those connections that we can? Maybe a little randomness is in order?

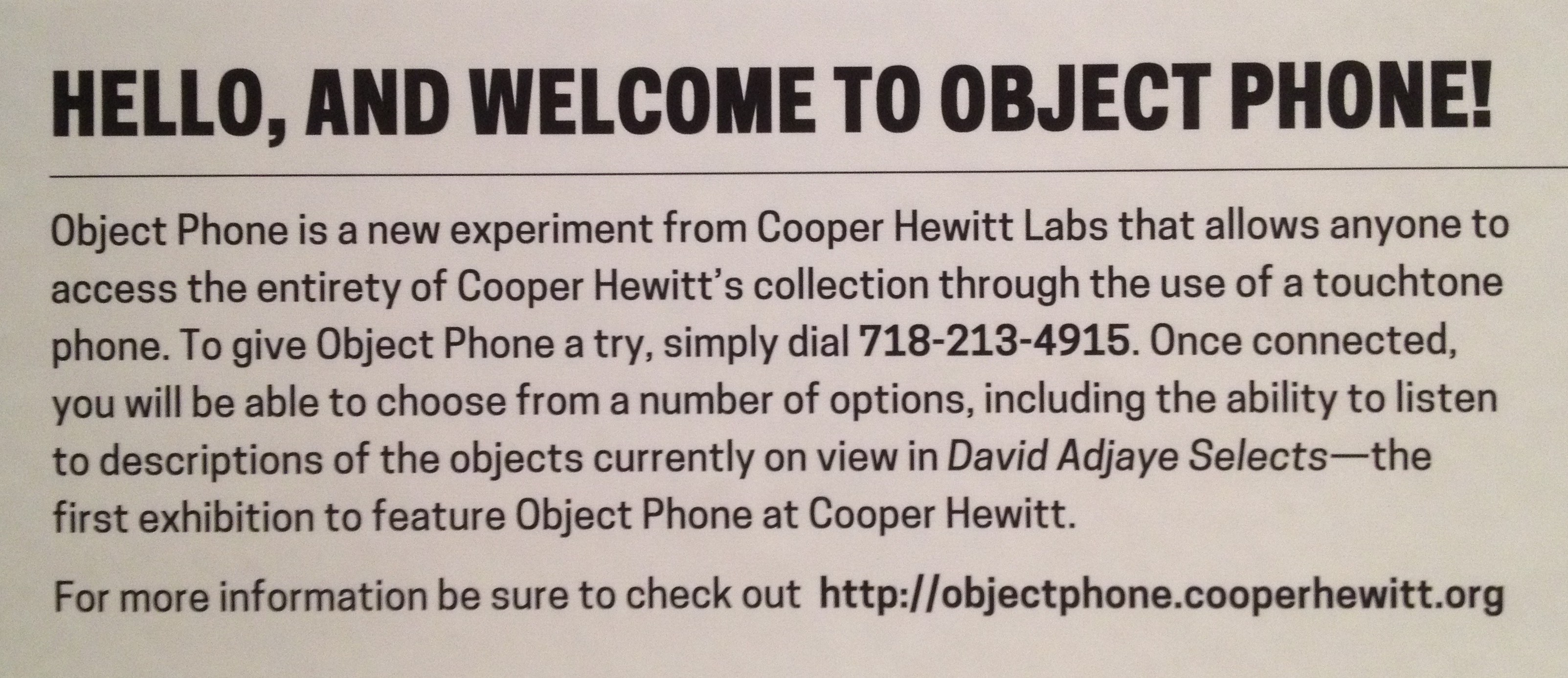

If your artworks could tweet, what would they say? (Object Phone from the Cooper Hewitt, described in a blog post by Micah Walter)

If this sounds like a lot of work, it is! All the more reason we need to make intentional decisions about storage, archiving, tagging, connections, what we're going to gather and how long we're going to keep it, and why, AND WRITE IT THE F*** DOWN. Your future archivists will thank you.

The classic internet-of-things joke is the fridge ordering milk. So will an art object start a ticket because it needs to be conserved? Will a label tell you people want to read it in Chinese? Does a gallery tell you, send more people over this way! Are some objects at risk of becoming digital have-nots?

If the museum is no longer the container that we think it is—a term used more commonly with content strategy—if the objects are already tagged, and it's just a matter of the connections, are we really that far from the lightning strike that sends the primordial ooze self-replicating?

Obviously there are infinitely many ways to link objects and data around the museum, more than we could ever really hope to capture before the next taxonomy comes along. Again, data has to be a behavior. We need to play proposal thought experiments: if we tag every label, for instance, so it's in our system (whatever that means), what would that take? Why is it important? Who would, could use it?

oh all the lovely data points

Prove this is important. Then, find a donor. We need data about our data, to get an intrinsic sense of what needs to be kept and what discarded. That will take more of a sense of experimentation in our museums. Put people in a position to succeed, make them want to tag it. Give them the time and resources to tag it. Make it FUN. Your colleagues will thank you. The art? We can only hope that the objects make for benevolent rulers.